An Opening Shot in the City’s Epic Freeway Fight.

Back in 1967, when I was a student at Catholic University, my friend Jim O’Brien and I noticed a lot of construction equipment at the Taylor Street bridge on the north end of the campus. Jackhammers and cranes were working on the center of the span. We didn’t know the reason for the demolition, since the bridge seemed to be in pretty good shape. Nonetheless, on a weekend when the workers were gone the two of us walked up and sat down with our feet dangling over the broken edge. We hung out for awhile, drank a couple beers and watched the trains roar by on the B&O rails. It was somewhat dangerous I suppose, but provided a lasting memory.

Over the years I learned the history of the bridge, and there are some interesting facets to it. Back in the mid-1930s, the District government was actively trying to get rid of the last grade crossings within city limits. As traffic increased, so did the danger of car and train collisions at the crossings, which were happening with more frequency. The Michigan Avenue bridge was built in 1937 to great fanfare, eliminating the grade crossing there. That left only one, about three quarters of a mile north, where Bates Road crossed the track.

Bates Road was a very old thoroughfare, part of the colonial era Georgetown-Bladensburg Road. Today it has been absorbed into Varnum Street on the east side of the tracks, and Fort Totten Drive on the west side. In the 1930s the crossing at the B&O tracks had a reputation as the most dangerous in the city. John Hurley, president of the Michigan Park Citizens Association, expressed his fears to the Evening Star:

This grade crossing is the last of its kind in the city of Washington and it takes a yearly toll. To us, who use Bates Road every day, it has become a thing of terror.

There had been three deaths there in the two years prior to 1939, and city government finally appropriated funds for a bridge. Planners decided that Taylor Street would make a better crossing point than Bates Road, so the new bridge was constructed two blocks south of the old grade crossing, which was then closed off. Hawaii Avenue was also built on the west side of the tracks to hook into the new bridge. On April 20, 1940, with a light mist coming down, the Taylor Street Bridge was formally opened. There was some speechifying and a parade, and the first cars crossed just as a train passed beneath, blowing its whistle. The new crossing made an immediate impact. Michigan Park had been growing rapidly since the 1920s and the Turkey Thicket apartment complex opened in 1937, increasing the population substantially. The bridge made access to the west far easier and safer for the new residents than the old grade crossing.

So why were they tearing the bridge down only 27 years later? Because they needed to make room for a new freeway. Eight lanes of new freeway. Plus two new rail tracks for a subway. It was the first work to be done on a major urban transportation plan that became a political fight of gigantic proportions and a defining moment for the District of Columbia.

Congressional planners had been thinking about adding highways for decades, but demographic changes in the late ’40s and early ’50s brought new impetus to the process. Initially, there was the Great Migration that saw six million African Americans leave the south and spread across the north, midwest, and west. In Washington in 1947, when the Supreme Court ruled that race-restrictive housing covenants were not legally enforceable, the gates opened for African Americans to live in neighborhoods formerly closed to them. “White Flight” took off, as streams of White residents left the city. Brookland went from a majority White to a majority African American neighborhood in the span of twenty years. With so many people moving to the suburbs, Congress decided new highways were necessary to allow those suburban dwellers easy access to downtown. What they came up with would carve the city into pieces.

There were many iterations of the highway plan over the years. The map above is from 1966. What is labeled “Central Potomac River Crossing” was to be the site of the new Three Sisters Bridge, bringing I-66 into the District. It would become a major bone of contention. The North Leg would decimate U Street and Shaw. For us in Brookland, the most controversial leg of the plan was the North Central Freeway. It would cut through Brookland and Takoma Park and effectively isolate the eastern neighborhoods from the rest of the city. Altogether, thousands of homes and businesses would be destroyed, most in Black neighborhoods. Here’s a closer look at the portion through Brookland from a later plan. Notice Taylor Street at the top of the map and you can see why they needed to lengthen the bridge there:

Naturally, opposition developed almost immediately. The city had an appointed mayor and council in 1967, essentially powerless against Congress, in particular the chair of the District appropriations committee, Rep. William Natcher (D-KY), who was avidly pro-highway. He held the pursestrings for any subway system as well, which is what the city really wanted.

Citizens, both Black and White, were outraged by the highway plan. The Emergency Committee on the Transportation Crisis was formed with Reginald Booker as its chair, having been encouraged by Sammie Abbott, an activist with a long pedigree of anti-highway sentiment. Booker was African American. Abbott was White. Joined by people like Julius Hobson, Marion Barry, Simon Cain, Tom and Angela Rooney, Fred and Ann Heutte, and many others, the E.C.T.C. became an effective interracial cudgel against the highway promoters.

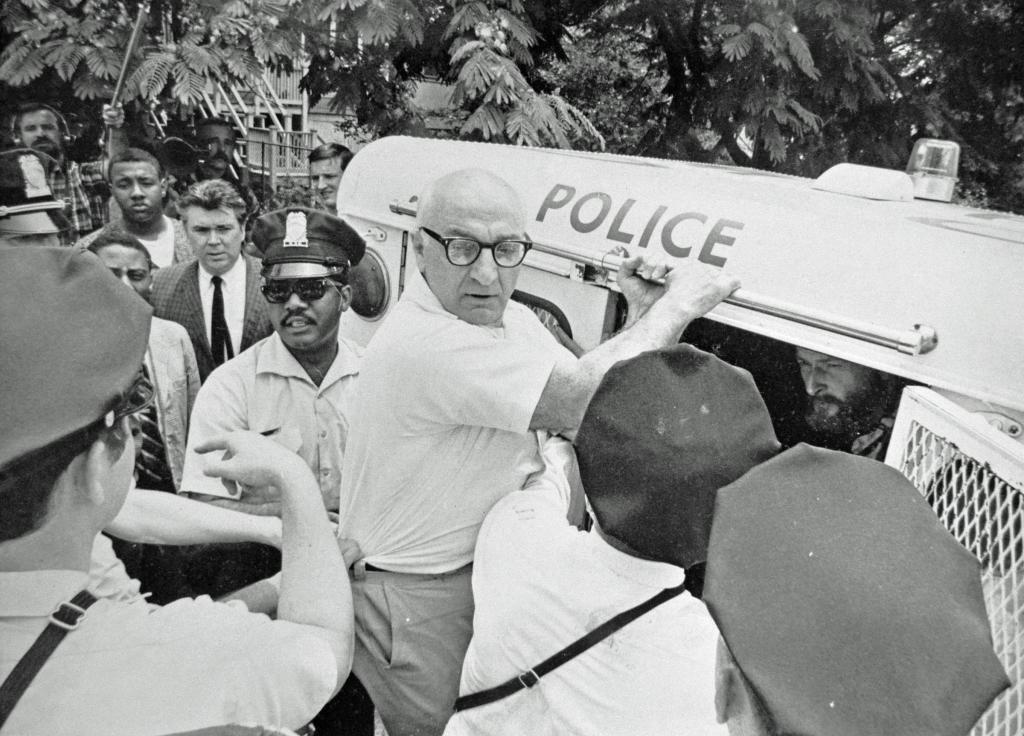

About the same time the Taylor Street Bridge was being demolished, the city condemned a number of homes along 10th St. NE, between Rhode Island Avenue and Franklin Street. They were going to be demolished for the North Central Freeway. The tenants were forced out and the houses boarded up, but then the delays came. The E.C.T.C. staged an action in 1969 where they unboarded one of the houses and went inside, ostensibly to clean it up so it could be lived in again. The police were ready, and soon arrests were made.

Other protestors were using the courts, particularly lawyer Peter Stebbins Craig (right). He was part of a group called the Committee of 100 on the Federal City that were opposed to highway plans. Together with the D.C. Federation of Civic Associations and other groups, they filed suit in U.S. District Court. It was thrown out. They took it to the U.S. Court of Appeals. Their main argument centered on an 1880s era law that disallowed any District highway wider than Pennsylvania Avenue. In February 1968, they won the appeal. The ruling required a complete stoppage of work on the highways. Mayor Walter Washington, feeling the pressure of the public protests, didn’t contest the ruling and all work stopped, including on the Taylor Street Bridge, now half-demolished.

Photo from Evening Star, February 11, 1968. The bridge would sit this way, without the wooden structure over the tracks, for another two years. Reprinted with permission of the DC Public Library, Star Collection ©Washington Post

Natcher did not like the ruling nor all the protests, and used his legislative power to beat them back. With the 1968 Federal Highway Act, the city would be forced to build the Three Sisters Bridge and all the highways. Natcher declared that no subway money would be released until the highway plan was accepted and construction begun. Marion Barry said Natcher was a racist trying “to blackmail the city,” which he certainly was. At a contentious meeting on August 9, 1969, the City Council, afraid of losing the subway entirely, grudgingly agreed to Natcher’s terms. The protesters exploded.

In the photo above, members of the E.C.T.C. at the August 9th, 1969 City Council meeting shout at the members. Third from the left is Reginald Booker, fifth from the left is Sammie Abbott. Standing next to him with the pipe is Julius Hobson, a major District activist and mayoral candidate, and seated below him to the right is Marion Barry, then chair of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, DC Chapter.

Sterling Tucker, City Council Vice Chairman, tried to calm the anger with a bitter truth:

We do not have home rule, and there will be times, such as now, that awareness of our lack of power will be hard and cruel.

It was not enough for the protestors. Scuffles broke out and the meeting descended into pandemonium. Booker, Abbott, Hobson, and eleven others were arrested.

President Nixon’s Transportation Secretary, John Volpe, ordered work on the Three Sisters Bridge to begin. Protestors blocked the bulldozers and canoed out to the three rocky outcrops in the Potomac that would be the foundation for the bridge, displaying a large banner and disrupting the construction. Many arrests were made, and continued to be made as the protests went on in the following days. But a temporary restraining order was issued and work was stopped in the fall of 1969. The city was given until February 20, 1970, to recommend any changes to the Congressional highway plan or it would go into effect.

The City Council finally found some gumption, and with the February deadline days away recommended scrapping the North Central Freeway entirely. Natcher once again threatened to cut off subway funding. Transportation Secretary John Volpe recommended a new 16-month restudy of the North Central Freeway. The political tide seemed to be turning. The District resumed work on the Taylor Street Bridge, rebuilt to accommodate the new subway tracks, but not eight lanes of freeway.

In the late fall of 1970, I and a few friends hopped into Jim O’Brien’s truck and took our first drive over the newly completed span. We might have later consumed a few beers in celebration.

The freeway fight continued, and was soon joined by another heavyweight player. New lawsuits had been filed, and U.S. District Court Judge John Sirica, soon to be famous for his work on the Watergate case, ruled that all work on the Three Sisters Bridge be halted, because proper planning procedures had not been followed. The city appealed the decision, but it remained in limbo. Finally, in late 1971 Rep. Natcher succumbed to the pressure from Maryland and President Nixon and released the subway funds. It was almost over. The highways were scrapped from the city’s plan. Funds were diverted to the subway. And in 1972, the Supreme Court let Judge Sirica’s ruling stand and the Three Sisters Bridge was scrapped as well.

The District of Columbia gained home rule at the end of 1973, but it did not end Congressional supervision (some might say interference) in District affairs. Congress still has ultimate budgetary control, and all legislation is reviewed and can be blocked, and often has been, depending on the political leanings of Congress at any given time. But the freeway fight showed what power the ordinary citizens of the District can wield when they work together in a worthy cause. Thanks to those men and women, Black and White, who rose up in the ’60s and ’70s to challenge the power of the U.S. Government, Washington DC is one of the only major cities in the country not criss-crossed with highways. We owe them all a debt of gratitude.

Sources:

The story of the Washington freeway fight is more complex and fascinating than presented in this brief outline. There are some great documents listed below that flesh out the story. The most thorough is probably the 10-chapter examination by Richard Weingroff of the Federal Highway Administration. I found the article by Bob Levey and his wife, Jane Freundel Levey to be the most readable and enlightening. For 23 years, The Washington Post carried the daily column “Bob Levey’s Washington.” Jane Freundel Levey was the editor of Washington History magazine. No couple knows the city better. Finally, the coverage of the freeway fight in the Evening Star (available online at the DC Public Library site) was excellent and essential to my research.

Jaffe, Harry, The Insane Highway Plan That Would Have Bulldozed DC’s Most Charming Neighborhoods, Washingtonian, October 21, 2015

Jordan, Jemila, The Roads Not Traveled: D.C. Pushes Back Against Freeway Plans, Boundary Stones blog, WETA, 2015

Levey, Bob, and Jane Freundel Levey, End of the Roads, Washington Post, October 26, 2000.

Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, A Right to the City: Brookland, Fight the Freeways, Digital Exhibit, 2018

Weingroff, Richard F., The D.C. Freeway Revolt and the Coming of Metro, Federal Highway Administration, updated 2019.

Willinger, Douglas, A Trip Within the Beltway, 2010

This is a great narrative of the freeway fight. As a youngster, I wondered why the Taylor St bridge was torn down halfway and left unfinished for do long.

I had no idea it was related to the proposed freeway

A friend of my older brother Pat Green, whose name was Frank Smith (a well known Brookland character at the time) took the bridge “home” one night in a very drunken state. He fell onto the gravel train track bed below but thankfully lived to tell the tale.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was good to be at CUA during those days. As a freshman in Tom Rooney’s art class, I heard him announce one day, ‘I might not be here next week; I might be in jail.’

LikeLiked by 1 person

The absolute statement at the end of this piece (“Washington DC remains the only major city in the country not criss-crossed with highways”) is a bit hyperbolic. There were ‘freeway revolts’ in other cities as well, most well-documented in San Francisco. Most of the proposed network of freeways there weren’t built there either (and a few were removed after being built thanks to the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake).

It’s great we avoided this disaster in DC, but to say we are the only place where this happened isn’t historically accurate.

LikeLike

You’re right. I edited slightly.

LikeLike

Thank you. Great how you weaved the story of this bridge into the bigger history!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do you know who Taylor Street is named after? Also interested in Randolph and Shepherd Streets. Thanks 😊

LikeLike

I’m afraid I don’t. Back in the 1910s the city government coordinated the names of the streets, but I’ve not done the research to give you any answers.

LikeLike

ironic to have such forthright history of activism and now Brookland and Bloomingdale in our generation SO FAILED MISERBLY to save McMillan Park.. just so pathetic!!

LikeLike

Well, this is great reading, since I new old man smith, the Rooneys, and Anne Heutte.

Before she passed away, Anne gave me an original poster advertising the opening of the Monroe Street Bridge (1929), with all of its fanfare. In this case being so significant because it would bring the streetcar across the tracks and connect Brookland to downtown by the mass transit of the time. I was present several times when Anne started telling “The Freeway Fight” story. In particular, I remember her saying that the real beginning of the fight began when “old man somebody” went down to the tracks along 9th Street and sat down in protest and refused to move. I don’t remember who she said that was— it could be someone mentioned in the article, or not. She said that from that point on, there was a constant gathering that grew and grew. I just don’t remember the man’s name that she said went down to the tracks first, and just refused to move.

Maybe someone here knows who it was.

All important history.

I think it is also interesting to note how we are still fighting this fight with the “no trucks” battle along 13th Street and other streets in Brookland, with a refusal to enforce the laws. The old timers would say that this is the government still making us pay for stopping the freeway — Given that many of the n/s streets in the neighborhood serve as commuter routes, that the proposed highway would have taken care of.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for that story about our mother Anne Heutte. My father Fred Heutte and she did so much work as part of the Freeway Fight. I remember growing up and Sammie Abbott coming over to our house. I used to help my Dad to canvas the neighborhoods with flyers announcing hearings, stuffing envelopes as a kid. So many names in this story also about folks who to me were great people: Reginald Booker, Julius Hobson, Sammie Abbott.

LikeLike