The Journey of Jehiel Brooks, Pt. 3

Part 2, which covers his term as Indian Agent 1830-1834, is available here: Journey, Pt. 2

On March 25, 1835, Lewis Cass, Andrew Jackson’s Secretary of War, wrote to Jehiel Brooks about the Caddo confederation, now willing to sign a treaty, appointing him as commissioner “to treat with those Indians.” There followed three pages of instructions. Cass begins by outlining the extent of Caddo territory, noting that the border between Louisiana and Mexican Texas had not yet been formally established, but he should go ahead with the treaty anyway. Agreement on that border with the Mexican government would wait until after the signing. Cass estimated Caddo holdings in Louisiana were between 600,000 and one million acres of land. Then he broached the subject of payment to the Caddo:

I do not think it would be proper to allow them under any circumstances a sum exceeding one hundred thousand dollars (100,000$) for their claim. From their incumbent and improvident habits the immediate payment of any considerable portion of such a sum would not only be useless but injurious. You will therefore take care that not more than twenty five or thirty thousand dollars (25 or 30,000$) be paid to them at any one time. The residue may be paid by equal annual installments of between six and ten thousand dollars (6 and 10,000$). You will provide for the payment of whatever is allowed in such manner as may be most useful and agreeable to them, either in money, goods, domestic animals, agricultural implements or in such other articles as their habits and mode of life require. The whole sum to be given will be kept as far within the maximum of one hundred thousand dollars (100,000$) as justice to them and the circumstances of the case on a full investigation of it will permit. This part of the subject must be submitted to your discretion under the limitations I have stated.

The paternalistic tone of this message was in line with the tenor of the times. “Their incumbent and improvident habits,” is a reference to alcohol consumption, which was indeed a problem, caused mainly by White people trading illegally with the Caddo. It was one of the main reasons the Caddo nation was in desperate straits. Still, for Brooks, acquiring their land was the most important mission. A million acres at the maximum of $100,000 amounts to only 10 cents an acre, which Cass considered as “justice to them.”

The rest of his instructions included how Brooks would be paid, travel expenses, how he should structure the Caddo payments, informing him that a company of troops from Fort Jesup would be made available, and finally that he should keep a day-to-day journal of the negotiations and the final treaty signing.

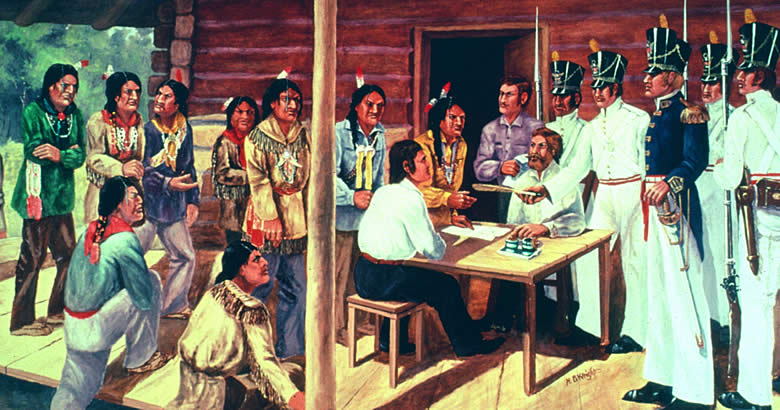

Brooks set out from Washington with his brother-in-law, 21-year-old Henry Queen, in tow. They arrived at the agency house on May 30, 1835. Larkin Edwards, the aged interpreter for the Caddo, traveled to all the nearby villages to inform them of Brooks’ arrival to begin treaty negotiations and that he had brought many presents for them. Brooks hired Larkin’s son John Edwards as interpreter, and Henry Queen as an assistant, charged with purchasing the provisions he intended to present to the Caddo. On June 26, 500 Caddo had assembled at the agency house. Tarshar, head chief, and Tsauninot, under chief, along with 23 other “chosen councilors” met with Brooks to hear his proposal. From the journal of Jehiel Brooks:

The council pipe was lighted and passed around and then I addressed them in the following manner:

Brothers: As we had been so long acquainted, I will, as on former occasions, proceed without ceremony to state the object of my present mission. In your address to your great father, the President last fall, which I presented for you, you offered to treat with him for the sale of all our (your) land that shall fall within the United States when the line from the Sabine to the Red River dividing Mexico from the United States shall be marked out, be the quantity more or less. He was well pleased to hear it and has sent me to make the purchase provided we can agree as to the price and the conditions of payment. And as the country, if purchased of you, will be for the White men to live in, it will be required for the Caddo to remove out of it in a reasonable time after your great father shall have approved of the bargain we may now make.

Brothers: Knowing your wants from a residence among you, I come prepared to alleviate them and to place you in a state of independence when compared with your present destitution if you will but make use of a little prudence. But I am told you have changed your minds and do not intend now to part with this country. And, although I know you have received such advice from many who fain would have you consider them as your exclusive friends, still I do not believe that you are so blind to your true interests as to follow such advisers who cannot, if they would supply your wants, but whose only aim is to deceive that they may yet a little longer rob you of the little you from time to time accumulate by the chase. On the other hand, I have never deceived you and you know it; and am again sent as your friend to obtain that from you which is of no manner of use to yourselves and which the Whites will soon deprive you of, right or wrong, and am ready to give you for it what you cannot otherwise obtain, or long exist without, in this or any other country. I am instructed to deal liberally with you which coincides with my own feelings and wishes. Brothers, I am done; my business is stated; I await your answer.

There were indeed numerous people trying to convince the Caddo to stay and not sell their land. They were almost entirely illegal White traders, who saw they were about to lose a major source of income. The troops from Fort Jesup were charged with keeping those people, and any other unwanted guests, away from the negotiations. But the Caddo were not easily duped, as is evident in under chief Tsauninot’s reply to Brooks:

Brothers: We salute you and, through you, our great father who has sent you again with words of comfort to us. We are in a great want and had been expecting you to bring us relief; for you told us before you departed last fall that you had no doubt our great father would treat with us for our country and would supply us with things of much more value to us than these lands which yield no game…It is true that we have been advised by many not to make a treaty at all; that we should be cheated out of our land and then driven away like dogs; and we have been promised a great deal if we would refuse to meet you in council. But we have placed no reliance on the advice and promises of these men because we know what they want and what they will do; and we have warned our people from time to time not to heed such tales, but wait and see what our great father would do for us. We now know his wishes and believe he will deal justly with us. We will therefore go and consult together and let you know tomorrow morning what we are willing to do.

For Brooks, it was a propitious beginning. He was now hopeful for a good outcome. At 10am the next day, the Caddo council returned with their answer. Tsauninot spoke:

Brother: We have stated to our people the wish of our great father as expressed by you to us yesterday and that you had brought a great many rifles and powder and lead in abundance, axes, tomahawks, knives and flints, blankets, cloths and calicoes, and beads and shawls, and, indeed everything we are so much in want of; all of which you would give to us at once if we would deliver up this country to the White people. They hung down their heads and were sorrowful. Then our head chief, Tarshar rose and said:

My Children: For what do you mourn? Are you not starving in the midst of this land? And do you not travel far from it in quest of food? The game we live on is going further off and the White man is coming near to us; and is not our condition getting worse daily? Then why lament for the loss of that which yields us nothing but misery? Let us be wise then and get all we can for it and not wait till the White man steals it away little by little, and then gives us nothing. This is my advice; if you think it good, rise up and dance the corn dance, but if bad, let not the drum be beaten tonight and we will depart for our homes tomorrow. He ceased; and, after a short pause, they all sprang to their feet with cries of satisfaction and proceeded to perform the dance with unusual animation.

Tsauninot then continued, bringing up some issues that would eventually come to haunt Brooks.

We are now at liberty and willing to make a treaty; but we cannot sell all the lands in the boundaries of our territory on this side of the line you mentioned because we gave many years ago to our great friend, François Grappe and to his three sons then born, four leagues of land in the southeast corner of our territory bordering on the Red River. And we have given to Larkin Edwards, our best friend since the death of Grappe, one mile of land to be taken wherever he may choose. He never sends the Red men from his door hungry. He is old and feeble and has no means now to live as formerly when our great father paid him to talk for us.

Those two tracts of land were referred to as “reserves,” and the U.S. Government frowned on them. In dealing with Native Americans, the government wanted any exchange of land to only be between the tribes and the government. But it appeared that Jehiel Brooks was pushing for those two reserves to be included in the treaty. The Caddo had already signaled their intentions to reward Larkin and the Grappes in the memorial they sent to President Jackson a few months previously, which Brooks helped compose. The gift to Larkin Edwards was known as a “floating reserve,” in that he could choose anywhere within Caddo territory to claim the 640 acres. The Grappe Reserve was specific to a tract of land on the west bank of the Red River, a large site, variously reportedly as 18,000 to 34,000 acres, bordered on the south by the Bayou Pascagoula. It was known as Rush Island. There were White settlers there, who Brooks had tangled with during his tenure as Indian Agent. The Caddo said that they had gifted the land to Grappe in 1801, in front of the Spanish authorities in Natchitoches.

The map below by Nancy Tiller depicts the extent of Caddo land in 1835. It also shows a number of Caddo villages and the variety of proposed dividing lines between Mexico and Louisiana. Rush Island is outlined in red. Though they are on the map to assist in location, Shreveport, Greenwood, Marshall and Carthage did not yet exist in 1835.

François Grappe is an obscure but fascinating historical figure. Also known as Touline, he was the son of an early French settler and a Caddo wife (although some records indicate she was half Chitimacha). Grappe was literate, and could speak numerous languages, including many of the Native American tongues. In that capacity he served the French, Spanish, and American governments in Louisiana. He appears off and on in the historical records, fighting with Spanish troops to help the Americans in the American Revolution, serving as an interlocutor between the tribes and whichever government was in power, guiding parties of settlers and explorers through the wilds of the area, and starting a vacherie, or cattle ranch, in 1787, that supplied meat to many throughout northwest Louisiana. His family was centered near Campti, on the eastern side of the Red River. He worked closely with some of the Indian Agents as well, starting with John Sibley, who wrote that Grappe was “deservedly esteemed by the Indians, and all others, a man of strict integrity, [who] has for many years, and does now, possess their entire confidence, and a very extensive influence over them.” Grappe died in 1825, before Jehiel Brooks began his term in 1830, though Brooks was certainly aware of his reputation and influence. In response to Tsauninot’s statement, Brooks peppered them with questions about the reserves:

I then put the following queries to them:

Who among you were present at Natchitoches, before the Spanish authority, and consented to this gift of land to Grappe and his sons?

The following members of the council answered they were, namely: Tarshar, Tsauninot, Tennehinun, Oat, Kianhoon, Ossinse, Hiahidock, Kardy, Aach, Tiatesun, and Chowabah.

What had he done to entitle him so much to your friendship and favor?

Answer by Tarshar. His father was a Frenchman who lived with us many years and married one of our women by whom he had François. Sometime after he left us and took his son away with him. But his son returned when he had grown to manhood and lived with us many years. He was our interpreter with the French and Spaniards and afterwards with the Americans while the agent resided at Natchitoches. He was wise and good and always the Caddoes’ best friend. It was all we could do to show our friendship for him and his children.

Why give so much to them and so little to Mr. Edwards?

Answer by the same. Because the Spaniards never gave less than one league to an individual and Mr. Edwards asked for no more than one mile.

I have asked these questions because your great father and his head men are opposed to Indian reservations as there are always bad men seeking every opportunity to cheat the Indian out of everything he possesses. But I will state your wishes in these particulars, in such a form that if they are not approved of they may not effect our main bargain. I am ready now to hear the price you ask for your land and the mode of payment that will please you best.

Tsauninot replied: We expect that you will make us an offer as we know not how to fix a price.

Brooks then told the Caddo to take the time to meet among themselves and return when they were ready. The next day, June 28, a few White men were discovered in the Caddo encampment. They were sent away and Brooks had the military post guards to keep out anyone without a pass signed by himself, the commissioner.

June 29. – The council was opened at 10 o’clock A.M. when Tsauninot said that they had decided on hearing a proposition from me. As I had anticipated such a decision, I said that I had fixed on a proposition and would state it to them at once. In the first place, I recapitulated their boundary lines and the present uncertainty where the Mexican line would cross from the Sabine to the Red River which might greatly enlarge or diminish our present mutual opinions of the quantity of land within the same. But the understanding between us is that, be the quantity what it may, when the line defining it shall be established by competent authority we now contract for and embrace it all, and for every part of your land contained within the boundaries as before stated; and you agree to remove, at your own expense, out of the United States.

In consideration of your cession of land and removal from it, the United States promise to pay you $80,000; $30,000 in goods and horses, and (as soon after signing the treaty as practicable) $10,000 per annum from September 1 next for the period of five years, to be paid in money or goods as you may now or hereafter think proper to direct. This proposition is founded on my knowledge of your country and your peculiar condition in relation to your localities and necessities and with my present ability to fulfil; and now I assure you that I consider it not only liberal, but generous toward you under existing circumstances. And that you may consider the whole proposition well, I will await your decision till tomorrow. The council adjourned accordingly.

The $80,000 offer was under the maximum Lewis Cass had set, and Brooks was sure he would be pleased. Perhaps he also expected the Caddo to come back with a higher figure and bargain for a final price. They did not.

July 1. – The council was convened at 10 o’clock A.M. Whereupon Tarshar arose and said:

Brothers: We have considered well your proposition and have all consented to accept it. We will leave the country within one year from this time; and, as we may live some distance from this country, we will want to appoint some person to receive our annuities for us to do with it as we may from time to time direct. We therefore desire that it may be stipulated to pay our annuities in money. This is all we have to say. We are ready to sign our names to a treaty to that effect.

I Replied:

Brothers: I am very glad that we have agreed so well throughout and the negotiation has come to so speedy and satisfactory a termination. I will have the treaty ready for signing at 4 o’clock this afternoon, to which time we will now adjourn.

They had come to an agreement quite quickly. All that was left was drawing up the treaty papers and signing them. As he wrote out the treaty, Brooks split it into the main section, followed by two supplemental articles dealing with the reserves. If the supplementals were not approved by the President or Congress, the reserves could be removed without harm to the main treaty.

July 1. – At 4 o’clock P.M. the council assembled and the interpreter proceeded to translate the treaty and supplementary treaty into the Caddo language. After he had finished, I ask each member of the council, separately, if he understood the interpreter clearly and if he was ready to sanction it by signing his name; all of which being answered in the affirmative, the formality of signing was then gone through with in the presence of the subscribing witnesses. After the pipe was again passed round and congratulations exchanged on having closed the treaty, we shook hands and separated in friendship. The troops were then discharged from further duty at the treaty ground.

It was not quite as clear cut as Brooks describes here. There were witnesses to the ceremony who were also required to sign the finished treaty. The army had assigned 1st Lieutenant Joseph Bonnell as one of the witnesses. He asked Brooks if he could read the text before signing. Witnesses disagree as to whether Brooks refused or not, but Captain T.J. Harrison, Bonnell’s superior as commander of the military detachment from Fort Jesup, pronounced that they were only there to witness the treaty signing, not to read the actual contents of it. Bonnell was not happy, and would go on to publicly criticize Brooks for his handling of the process. Here is a link to the published text of the treaty:

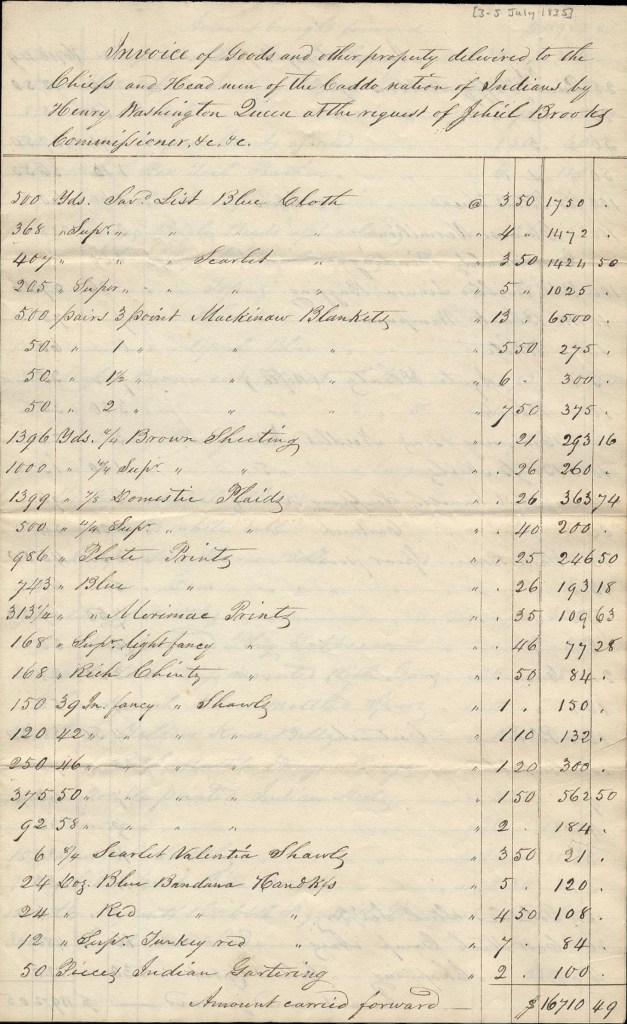

On July 3, $30,000 worth of goods and horses was turned over to the Caddo. The first page of the invoice Jehiel Brooks compiled, listing those goods, is on the right. (Click to enlarge.) In total, it was more than the Caddo had ever seen in one place at one time, and they left pleased, at least according to Jehiel Brooks:

The Indians, generally, expressed great satisfaction with everything they received and with the whole proceeding from the beginning to the ending. None went away dissatisfied.

Others were dissatisfied, however. The settlers on Rush Island saw a major part of their income about to disappear, and they would likely be ousted from the land as well. They had been kicked off the island before by George Gray, Brooks’ predecessor as Indian Agent, but Brooks treated them more gingerly when they returned, although he expelled settlers from other parts of Caddo territory.

His work done, Brooks, now a private citizen, left the agency house and traveled to Natchitoches, and some time in the weeks following, visited Jacques Grappe to talk about the reserve that had been granted to him and his brothers. Grappe seemed to be under the impression that Brooks could locate that reserve anywhere in Caddo territory, and could therefore give the Grappes scrub land, unsuitable for anything. Brooks offered to buy the tract for $6,000, though the purchase couldn’t be formalized until after President Jackson and Congress approved the treaty. Jacques Grappe agreed.

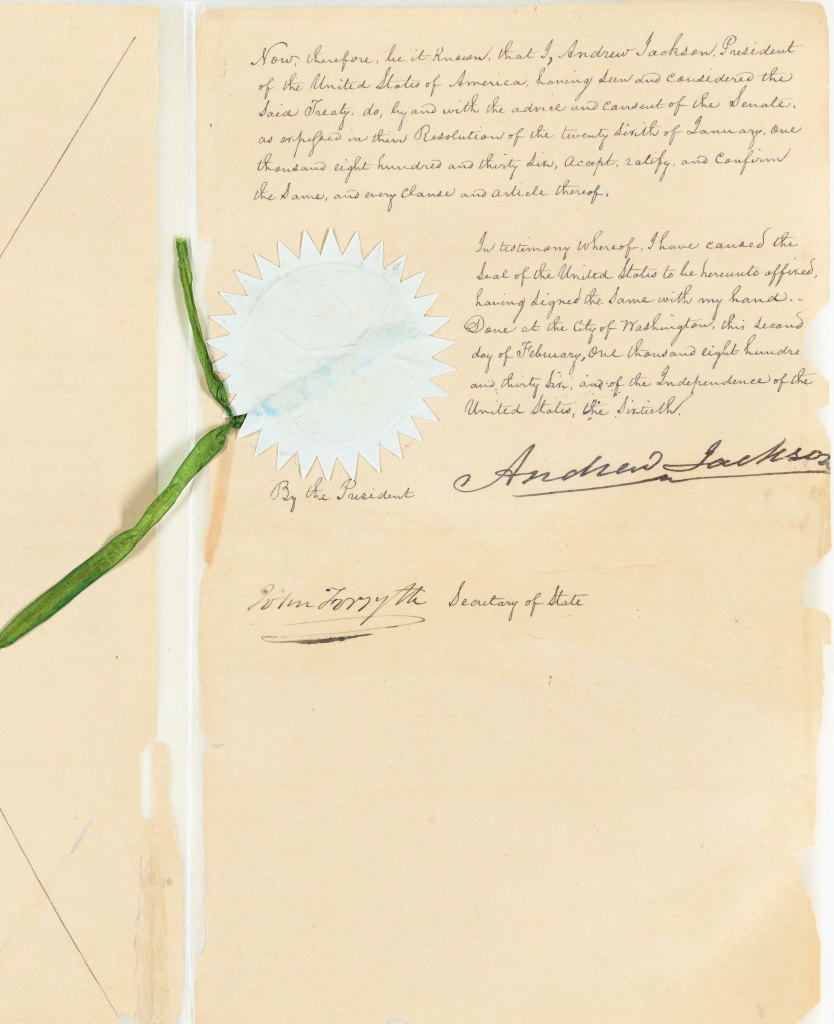

Brooks must have been on pins and needles during the months that followed. If Congress or the President declined to approve the two supplemental articles, the two reserves would be eliminated while the rest of the treaty carried through. Whatever deal he had made with the Grappes would be moot. So he must have been relieved when Congress approved the full treaty in January of 1836, and then the President himself signed it on February 2nd.

Now, therefore, be it known that I, Andrew Jackson, President of the United States of America having seen and considered the said treaty, do, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, as expressed in the Resolution of the twenty-sixth of January , one thousand eight hundred and thirty six, accept, ratify and confirm the same, and every clause and article thereof.

With the treaty fully approved, including the supplemental articles dealing with the reserves, the path was now clear for Brooks to obtain the Grappe land for himself, which was formalized the following January. Everything must have looked bright for Jehiel Brooks as he contemplated the money he would make selling those lands. But he was unaware of a letter sent to President Jackson in April:

Red River Raft, Louisiana, April 29, 1836

Sir: I have understood from a source that can be relied on that an extensive fraud has been practiced on the United States by the agent of the Government making a treaty with the Caddo Indians in this vicinity in July last. Believing it to be my duty to give information in such cases, I relate the facts to you as I have them; they are as follows: The interpreter officiating in making the treaty was sworn to secrecy. This fact I have from the interpreter himself (John Edwards); a reserve was made of four leagues of land commencing at the Pascagoula Bayou, running up the river for quantity, including all the land between the Bayou Pierre and Red River. By the meanders of the river, it will include a front of about thirty-six miles and contain not less than 34,500 acres of the best lands on Red River, being the tract described by me in a letter in reply to Elbert Herring, Esq., inquiring of me, under date of April 30, 1834. The reserve was made to a half-breed Caddo, or to his heirs, without any knowledge on their part of the transaction until after the ratification of the treaty when the agent came direct from Washington to Campté, the residence of the half-breed’s heirs, and bought from them the whole of the reserve at $6,000. It would have been sold by the Government for upwards of $150,000, if not double that amount. I am also informed that the principal chiefs of the Caddoes did not understand that such a reserve had been made. The witnesses to the treaty were also ignorant of such a clause having been in it. The opinion that prevails here is that it was a premeditated plan to defraud the Government as the half-breed alluded to had no claims on the Caddo tribe. Not one individual of the heirs, twelve in number, lived within sixty miles of the Caddo boundary. They are the children of a Negro woman.

Under all the circumstances, I am clearly of the opinion that an extensive fraud has been practiced on the Government by the agent. Still I may judge wrongfully and do not wish my name to be made use of as giving the information unless it may be necessary to investigate the case. I should not have meddled with the transaction did I not deem it my duty to do so. I beg you will therefore excuse my making this communication to you direct.

I am, Sir, with great respect, your obedient servant.

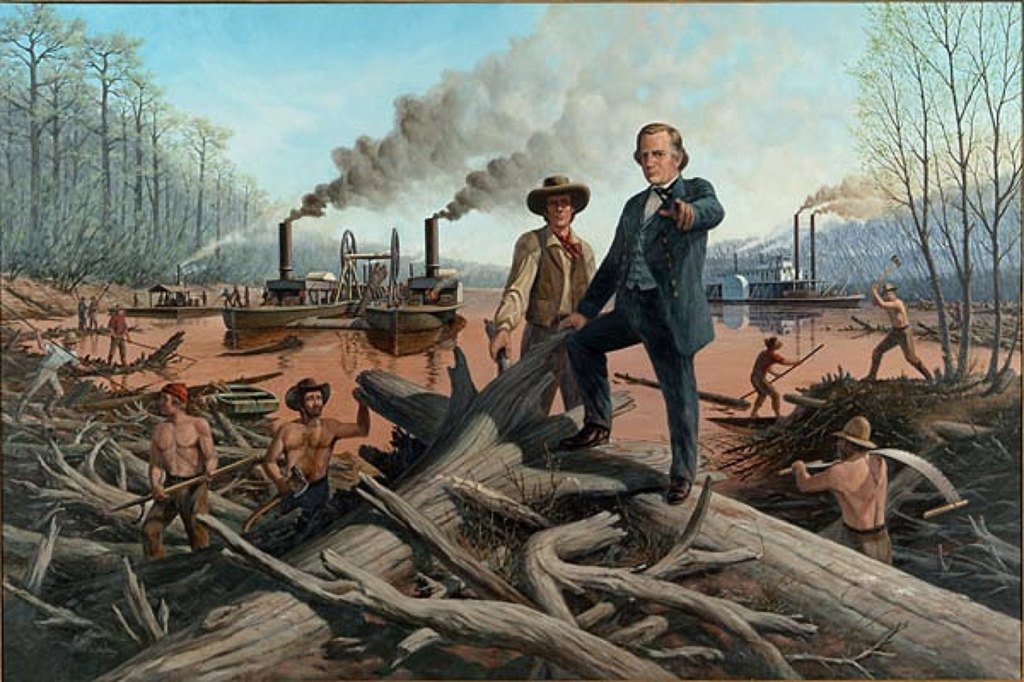

Henry M. Shreve

Captain Henry Shreve was a well-known man of distinction and energy. He had been appointed Superintendent of Western River Improvements in 1827. His heroic work clearing the Great Raft on the Red River was still ongoing and would open up great swaths of land for development. The fact that he had accused Jehiel Brooks of fraud drew immediate attention, and action.

The President has directed, that a copy of a letter received by him, should be transmitted to you, that you may present an explanation of the fraud therein charged to have been committed by you.

Elbert Herring was the Commissioner of the Office of Indian Affairs, and he did forward the letter to Brooks, but without Shreve’s signature, leaving Brooks to wonder who exactly was accusing him of fraud. Thus would begin 15 years of litigation, winding its way all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. That’s the next part of the story.

———————————————

Sources:

Brooks-Queen Family Collection. The American Catholic History Research Center and University Archives. The Catholic University of America. Washington.

Gates, Paul W., The Frontier Challenge: Indian Allotments Preceding the Dawes Act, University Press of Kansas, 2021

House Report 1035, 27th Congress, 2nd session. August 20, 1842

LaVere, David, The Caddo Chiefdoms: Caddo Economics and Politics 700-1835,University of Nebraska Press, 1998

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-1880, Caddo Agency, Record Group 75, National Archives and Records Administration. Washington, D.C.

Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824-1880, Red River Agency, Record Group 75, National Archives and Records Administration. Washington, D.C.

Lee, Dayna Bowker, Francois Grappe and the Caddo Land Cession, Journal of the North Louisiana Historical Association. 1989

Perttula, Timothy K., Dayna Bowker Lee, and Robert Cast, First People of the Red River, ResearchGate.net, 2008

Records of the Adjutant Generals Office, Letters Received, 1805-1889, Record Group 94, National Archives and Records Administration. Washington, D.C.

Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Letters Sent, 1824-1886, Record Group 75, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

Swanton, John R., Source Material on the History and Ethnology of the Caddo Indians, Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, 1942

Tiller, Jim, Jehiel Brooks and the Grappe Reservation: The Archival Record, Sam Houston State University, 2014

Tiller, Jim, The Shreveport Caddo, 1835-1838, Index of Texas Archaeology: Open Access Gray Literature from the Lone Star State: Vol. 2007 , Article 22

Webb /Clarence and Gregory, Hiram F., The Caddo Indians of Louisiana, Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism, Louisiana Archaeological Survey and Antiquities Commission