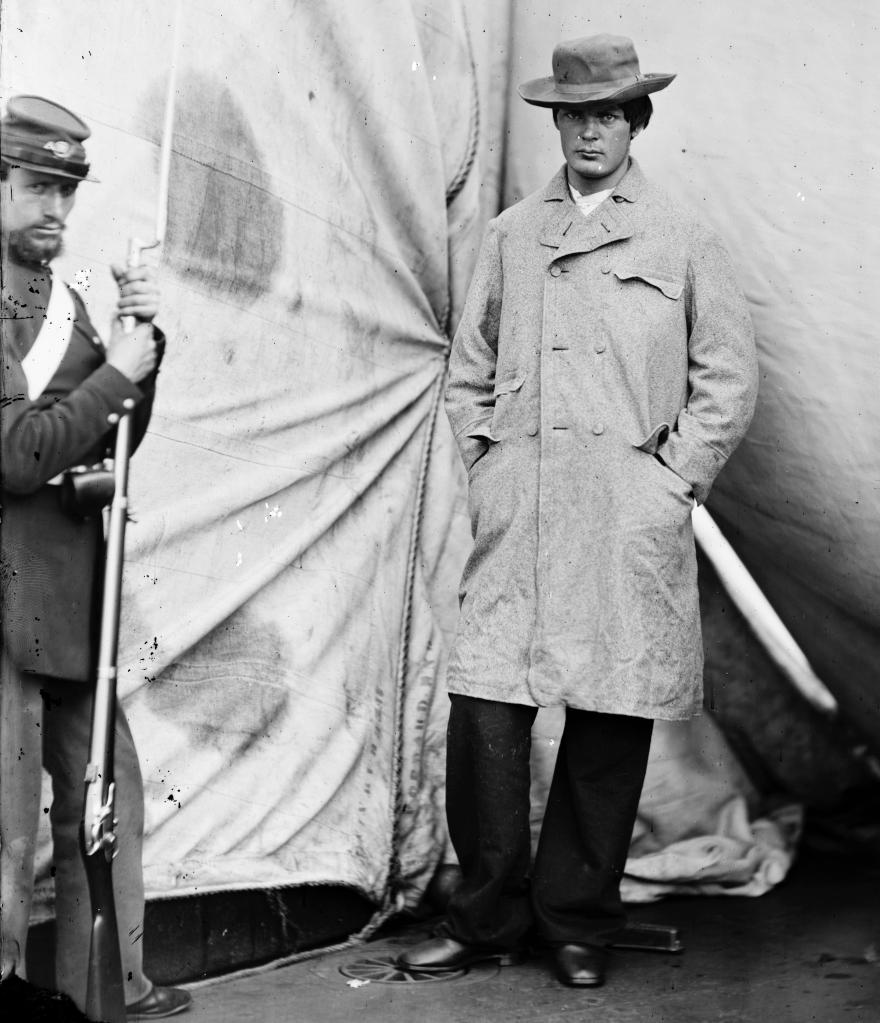

On April 16, 1865, Easter Sunday, Pvt. Thomas Price of the 3rd Massachusetts Heavy Artillery was patrolling on the military road between Forts Bunker Hill and Saratoga. It was only two days after one of the most shocking events in American history, when President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at Ford’s Theater and Secretary of State William Seward was brutally attacked in his home at Lafayette Square. None of the attackers had yet been captured though the manhunt spread far and wide, and everyone, particularly the military, was on high alert. During his search, Price ventured deeper into the woods and spotted something lying on the ground. It was a light-colored, double-breasted coat, and it seemed to have some blood stains on it. It was damp, but not soaked, even though it had rained Saturday afternoon. He checked the pockets and found riding gloves, a slip of paper with the words “Mary E. Gardner 419,” and a false mustache.

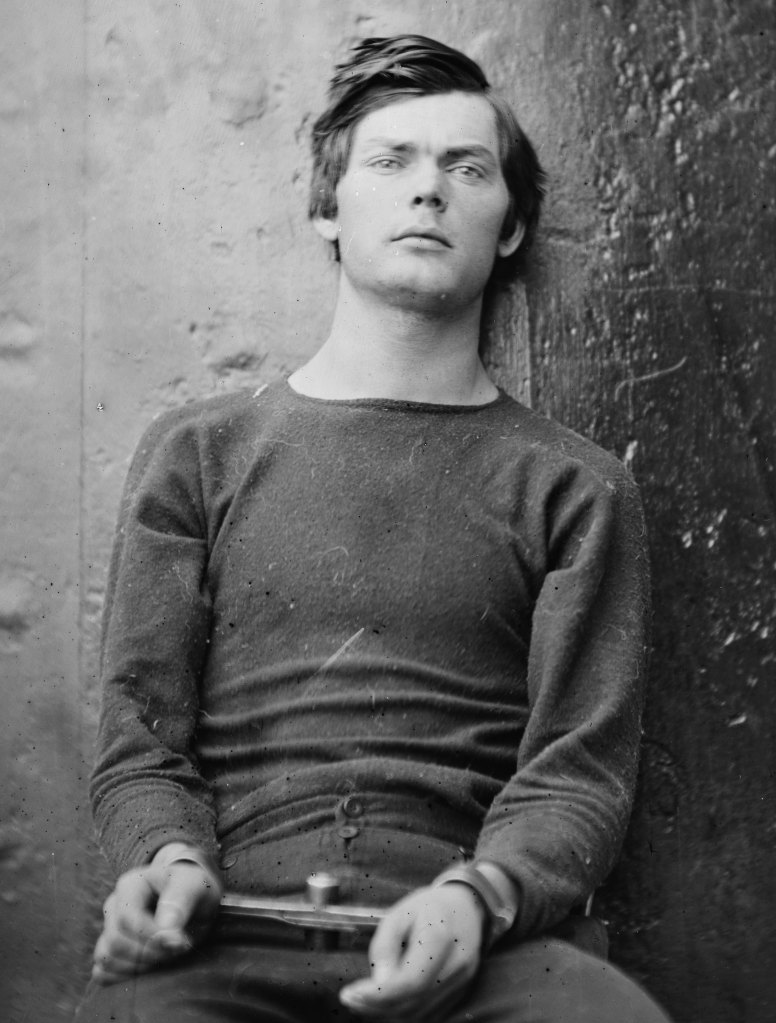

Pvt. Price knew this could be important evidence and brought the coat to his superiors. As it turns out, the coat belonged to Lewis Thornton Powell, 20 years old and a former member of Mosby’s Rangers, the Confederate guerrilla group. It would later be shown that he was the man who attacked Secretary Seward while Booth was murdering the President. So how did his coat end up in the future Brookland neighborhood? There is no firm answer, as Powell didn’t have much to say after his arrest, and others speculating on his movements are often contradictory.

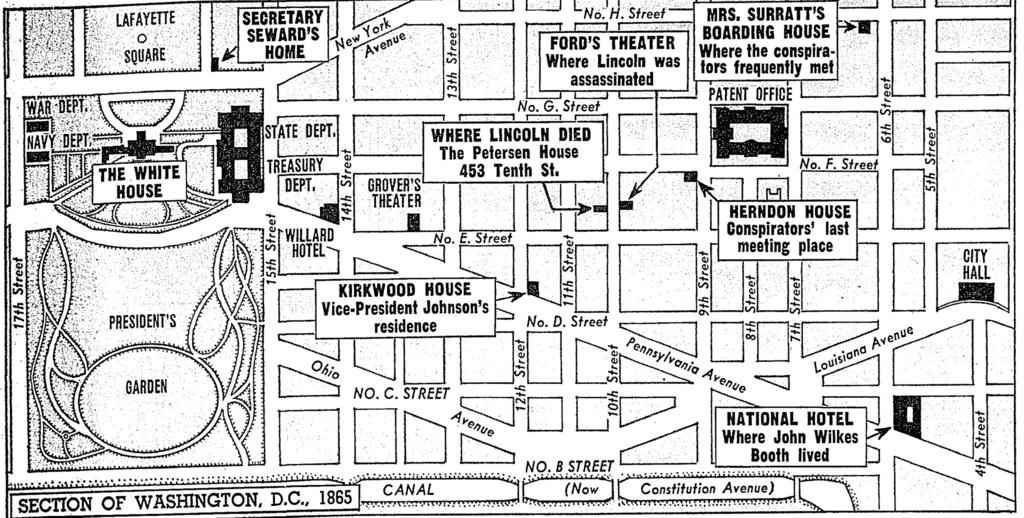

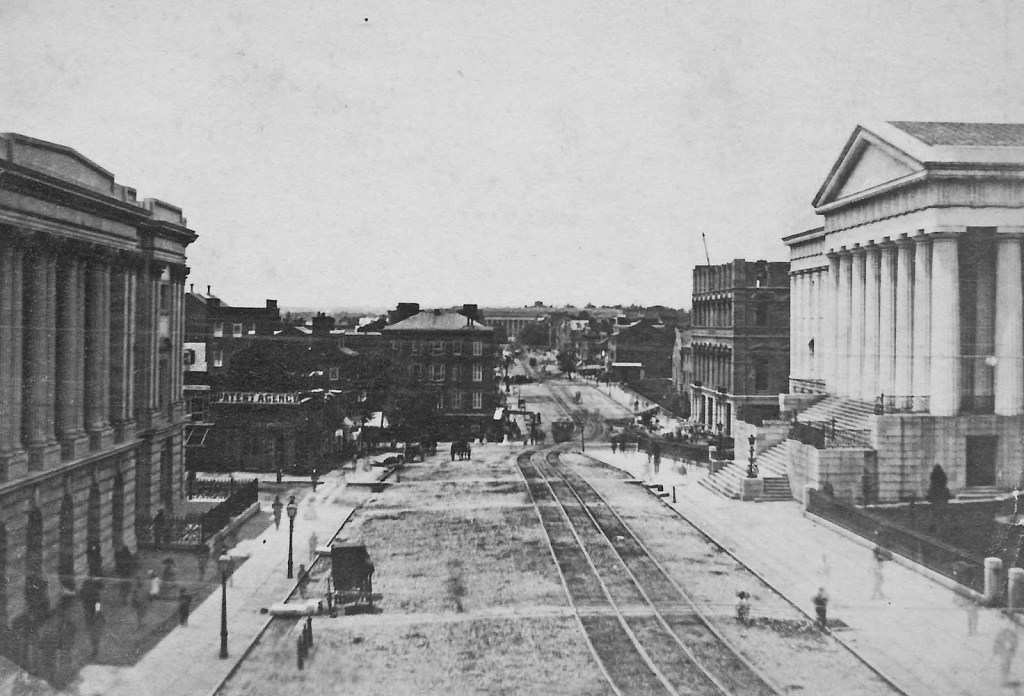

Here’s what we do know. On April 14th, at about 10pm, Lewis Powell left his room at the Herndon House, right around the corner from Ford’s Theater. The four primary conspirators, John Wilkes Booth, David Herold, George Atzerodt, and Powell had had their final planning session at the Herndon House just a little earlier. Booth would kill Lincoln, Powell would kill Seward, and Atzerodt was supposed to kill Vice President Johnson at the Kirkwood Hotel, though he demurred, to Booth’s anger. This map shows the various downtown locations involved in the conspiracy:

After the meeting, Powell got his horse, a large gelding blind in one eye, and headed off to Lafayette Square and Secretary Seward’s home. He knew Seward was sure to be there, as he was recovering from a bad carriage accident just nine days earlier, where his jaw and right arm were broken.

Dressed in a double-breasted light overcoat and wide-brimmed hat, Powell rode up to 17 Madison Place (then 15½ Street) and hitched his horse to a lamppost. It was a little past 10pm when he walked to the front door. He knocked, and the door was answered by William Bell, a young Black servant. Powell held up a small package with a prescription label on it and said he was sent by the Secretary’s doctor to deliver this medicine directly to Seward. Bell resisted, saying that Seward was likely already asleep. Powell brushed past him and began to clomp up the stairs.

Frederick Seward, the Secretary’s youngest son, came to the landing to see what the commotion was. Powell once again explained his supposed mission. Frederick said his father was asleep and he should leave the medicine with him. Powell insisted he needed to see the Secretary personally. Frederick once again asked Powell to leave. He seemed to agree and took a step down the stairs, then suddenly turned, held his pistol to Frederick’s head and pulled the trigger. The gun misfired. He then pistol-whipped him, fracturing his skull.

The two wrestled into the bedroom where Secretary Seward lay on his bed, his broken jaw encased in a wire brace, his broken arm hanging off the side of the bed. Secretary Seward’s daughter Fanny and Pvt. George Robinson, his army nurse, were in the bedroom. Powell drew his knife and slashed at Robinson, cutting him on the forehead, pushed Fanny aside and then jumped on the Secretary.

He stabbed repeatedly at Seward’s face, but the knife was deflected by the Secretary’s jaw brace so he was cut in the cheek on right side of his face and his neck on the left side. Pvt. Robinson then jumped on Powell, trying to wrestle him away. Powell hit him with the butt of his gun, dropped it, then slashed at him with the knife. The two continued fighting when Augustus Seward, the Secretary’s oldest son, ran into the room after hearing the yells and screams. He tried to maneuver the wrestling pair back out to the hallway. Powell managed to get free, ran out the bedroom door yelling “I’m mad! I’m mad!” and started down the stairs. There he ran into a clerk from the State Department who was delivering a message. Powell stabbed him deeply in the back and burst out the front door. He had left a bloody trail of violence behind him, though all of those he attacked would survive.

Powell dropped his knife in the gutter, mounted his horse, and although he wanted to gallop away, the horse did not, slowly cantering up 15½ Street, then picking up speed as it got to H Street. Witnesses then lost sight of him. No one saw him again until he appeared on the doorstep of Mary Surratt’s boarding house three days later. Where did he go in the interim? There are a few clues.

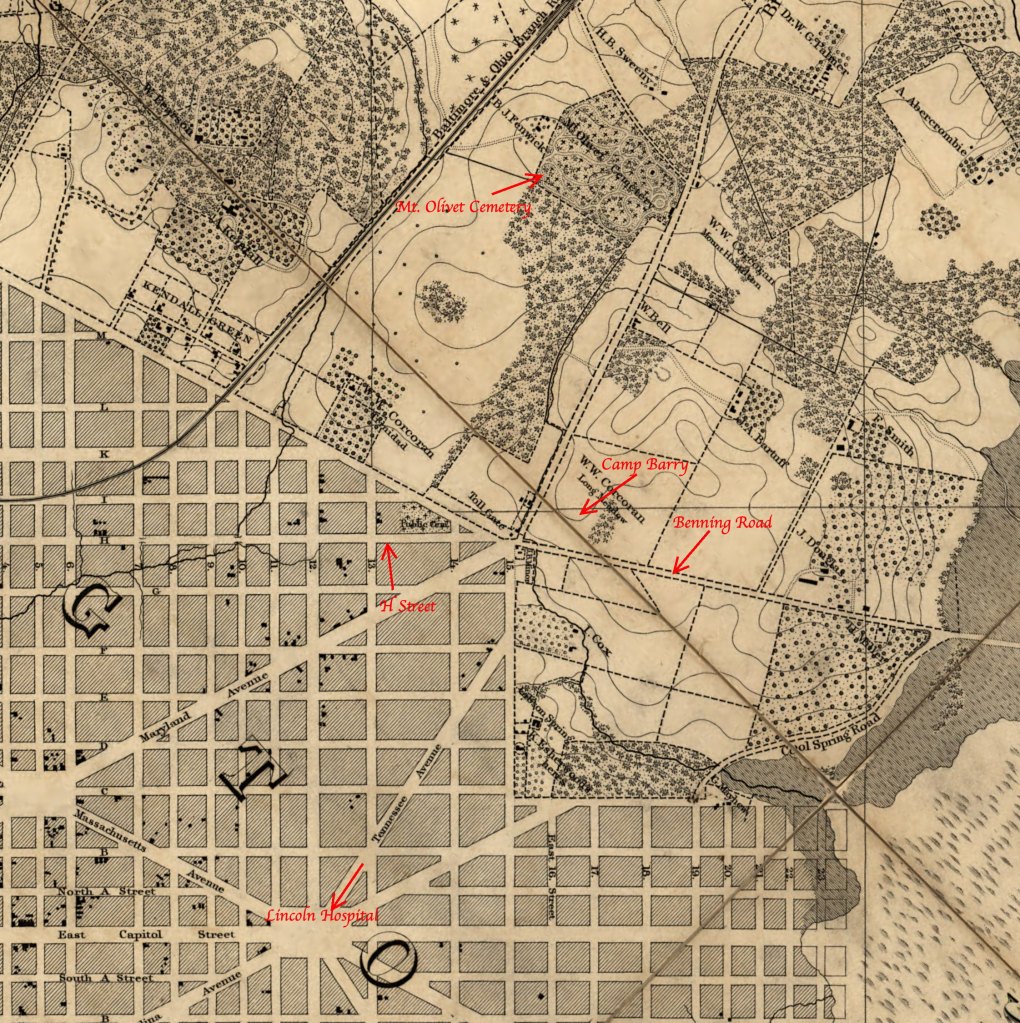

That night, actually Saturday morning about one a.m., a sentry found a riderless horse wandering near Lincoln Hospital on the road to Camp Barry. Lincoln Hospital was where Lincoln Park is today, around East Capitol and 13th Streets. The horse was sweating profusely, had a cut on its shoulder and mud on its knees, as if it had fallen. It was also blind in one eye. It was Powell’s horse.

Who Was Lewis Powell?

There have been thousands of books written about the Lincoln assassination and the planning, traveling, and funding that went into it. I won’t recount the whole story here, but a little background on Powell is called for.

Powell was born in Alabama; the family later moved to Florida, where he joined the 2nd Florida infantry in 1861. He lied about his age, claiming to be 19, when he was still just 17. He saw a number of battles, and was lightly wounded at Gettysburg, where he was captured and hospitalized . He met a nurse named Margaret “Maggie” Branson, a Southern sympathizer from Baltimore, who travelled to the battlefield to tend to wounded Confederates. The two began working together, nursing the soldiers while developing a close relationship.

Powell showed a talent for nursing, and while still a prisoner was transferred to West Buildings Hospital in Baltimore, Branson’s home town, where her family owned a boarding house that also served as a Confederate safe house. Maggie Branson had a younger sister, Mary, who quickly caught Powell’s eye. In 1863, Powell escaped from his captors, likely with the help of the Bransons. Through their connections, Powell eventually wound up with Mosby’s Rangers. He served with Mosby for a year and became a very effective guerrilla fighter. But the war took its toll, physically and emotionally. While delivering a prisoner to Richmond in November of 1864, Powell had a change of heart. No one quite knows the reason, though many historians have assumed it was because he realized at that point the South would lose the war.

Whatever the reason, he deserted on January 1, 1865, took a train to Alexandria, Virginia, claimed to be a civilian refugee, signed a loyalty oath to the Union under the alias of “Lewis Paine,” and headed to Baltimore and the Branson boarding house. But Powell wasn’t done with the Confederacy. He got to know a Confederate Secret Service agent and a number of other sympathizers during this period. In late January, maybe February, he met John Wilkes Booth in Baltimore and the two had lunch. At that point, Booth was already plotting against the President, though he was talking kidnapping, not assassination. The goal would be to exchange the President for thousands of Confederate prisoners. Powell was intrigued and Booth quickly recruited him. They bonded, and Powell soon became one of Booth’s main lieutenants. The other lieutenant was John Surratt, a cagey Confederate spy and courier. Surratt’s widowed mother Mary owned a tavern near present-day Clinton, Maryland, and a boarding house at 541 H St. in downtown DC. That boarding house was sometimes used for meetings and lodging by the conspirators.

Although Lewis Powell had sometimes stayed at the Surratt boarding house, his main residence while in Washington was at the Herndon House at the corner of 9th and F Streets. It was in his room there, just around the corner from Ford’s Theater, that the final planning session was held with the four primary conspirators.

Powell’s Escape Route

Where was Powell planning to go after his attack on Seward? Many speculated he intended to meet up with Booth and Herold in Southern Maryland, and cross over the Potomac into Virginia with them. But Powell had been in Mosby’s Rangers, who after an action tended to “skedaddle” in different directions to throw off any pursuers, and that seems most likely here as well. Powell later indicated he was heading to Baltimore, where he had friends and a network of Confederate safe houses. Either way, he was not aiming for the Navy Yard bridge that Booth and Herold took. Far more likely is that he was heading to the Benning bridge to cross the Eastern Branch (Anacostia River). The easiest way to get there was to go straight across the city on H St, which ran into Benning Road. Powell may not have realized that the bridge was closed off after 9pm, and he would have to talk his way past the guard if he expected to cross the river. Nonetheless, after racing across the city, it appears he got close to the intersection with Benning Road when his horse stumbled and threw him, perhaps knocking him briefly unconscious. The horse limped away, to be discovered shortly afterward about a half mile away on the road to Camp Barry.

Powell, now on foot and hurting from the fall, realized he couldn’t stay on the roads. Army troops were alerted and beginning to patrol, as well as Metropolitan Police. So he made his way in the forested areas north of Boundary Road (Florida Avenue), which were numerous. He might have hidden in Mt. Olivet cemetery for the night, or might have pushed on further. The longer he took, the more soldiers were patrolling, and the ring of forts in this section of Washington would be difficult to get past. According to reports after he was captured, he spent two nights hiding in various trees, sometimes close enough to hear soldiers’ conversations as they walked below. Although there were many confederate sympathizers in this part of town, including the Brooks and Queen families, there is no record of him trying to contact anyone for help. At some point, probably early Sunday, he ditched his blood-stained coat near the road leading to Fort Bunker Hill.

By Monday, after three days of hiding, Powell was starving and desperate, and decided his only choice was to head back into the city and the Surratt boarding house, where he might find shelter and food. It was a mistake. Authorities had already been alerted to “strange goings-on” at the Surratt House, and sent Metropolitan Police there on April 14th. A second raid was held on the evening of April 17th, this time by Federal authorities. The house was searched and all the residents, including Mary Surratt, were arrested and held there for questioning.

Meanwhile, Powell had secured a pickaxe, likely stolen from one of the farms near where he discarded his coat. The farm of Colonel Brooks was the closest to that spot, so it is possible he got it from one of the outbuildings behind the mansion. Powell had lost his hat in the fight at the Seward house, but since men did not go without a head covering in that era, he tore off a sleeve from his undershirt and fashioned it into a skull cap. Disguised as a laborer, he then made his way back into the city and the Surratt House, arriving around 10pm. Knocking on the door, his eyes went wide when he was greeted not by Mary Surratt, but a group of Army investigators instead.

When asked what he wanted, he mumbled something about being a laborer who Mary Surratt hired to dig a ditch. The investigators were immediately suspicious, given the late hour and the man’s strange garb. They called over Mary Surratt and asked if she knew the man. She lied and said she had never seen him before and did not hire him to dig anything. There was a certificate in his pocket with the name “L. Paine” on it. He was brought to Army headquarters, where he was thoroughly interrogated. William Bell, the young African American servant who answered the door of the Seward residence for Powell the night of the attack identified the captive as the same man. Powell was arrested, and brought to the ironclad Saugus, which was moored at the Navy Yard. There he was put in manacles and held below deck to await his fate.

Trial and Execution

Meanwhile, the Army had arrested a raft of other suspects and witnesses. George Atzerodt was arrested in Germantown, Maryland on April 20th. John Wilkes Booth had been killed on April 26th at the Garrett farm in Virginia. His companion David Herold surrendered and was in custody. John Surratt fled to Montreal, Canada. He wouldn’t be arrested until the following year. On April 29th, Powell and the other prisoners were relocated to the old penitentiary on the grounds of the Washington Arsenal at Greenleaf Point. The trial was set to begin in May, but it wouldn’t be held in a civilian court. On May 1, President Andrew Johnson decreed a military tribunal would take place and appointed nine officers to oversee the trial. There were eight defendants in all: Powell, David Herold, George Atzerodt, Mary Surratt, Samuel Mudd, Michael O’Laughlen, Samuel Arnold, and Edman Spangler. Because of papers identifying him by his alias Lewis Payne, Powell was tried under that name. It wasn’t until much later that he was formally identified as Lewis Powell. After a month and a half of testimony from 347 witnesses, all eight defendants were found guilty of conspiracy. Arnold, Mudd and O’Laughlen were given life sentences. Spangler, six years. Powell, Surratt, Herold and Atzerodt were condemned to death.

The executions were set for July 7, 1865. The four condemned didn’t learn of their fates until the night before. Generals Hartranft and Hancock came to their cells to inform them. Powell, expecting the death sentence, was calm and thanked the generals for their fair treatment, and said he was sorry for what he had done. Later that night he was visited by Rev. Abram Dunn Gillette, whom Powell had asked for. He was remorseful, saying he began regretting his attack the moment he left the Seward house. The next morning the prisoners could hear the gallows being erected and a few broke down in tears. The sentence was set to be carried out at one pm.

As the hour approached, the condemned prisoners were led from the prison to the gallows. All seemed weak, needing support, except for Powell, who briskly walked over and up the steps. His hat blew off, and Rev. Gillette picked it up and placed it back on his head. “Thank you Doctor,” Powell said. “I won’t be needing it much longer.” The prisoners were seated while guards bound their legs. Rev. Gillette then offered a prayer. Listening to him, Powell shed a few tears. The prisoners stood up and shuffled their way forward. The nooses were placed around their necks and hoods over their heads.

The captain in charge clapped his hands three times. On the third clap, the guards stationed below knocked out the supports for the trap doors. The doors swung down and the four prisoners fell about five feet. Powell lasted the longest, his body twitching and thrashing for five minutes. Twenty minutes later, all four were pronounced dead. They were buried in the Arsenal yard, just a few feet from the gallows.

One hundred sixty years after his death, Lewis Powell remains an enigma. Was he a brutish, violent beast, or a caring, compassionate nurse? A canny Confederate spy, or a thuggish young assassin, simply obeying orders? Historians have been speculating about him since the night of the assassination. There are records, and various reports, but there are lots of holes in the information continuum as well, allowing for multiple interpretations. That goes for the night his escape plan went awry as well. With so little information coming from him after his arrest, speculation abounds. My account is one more speculation.

The sources below contain much more detail about the plot to assassinate Lincoln and the men and women involved. I also consulted numerous period newspapers and maps during my research.

Sources:

Doster, William E. Lincoln and Episodes of the Civil War. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1915.

Edwards, William C. and Edward Steers, Jr., ed. The Lincoln Assassination: The Evidence. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2009

Kauffman, Michael W. American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies, New York, Random House, 2004

Ownsbey, Betty J. Alias Paine: Lewis Thornton Powell, the Mystery Man of the Lincoln Conspiracy. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1993

Pitch, Anthony, “They Have Killed Papa Dead!”: The Road to Ford’s Theatre, Abraham Lincoln’s Murder, and the Rage for Vengeance, New York, Skyhorse Publishing, 2008

Poore, Benjamin Perley, Conspiracy Trial for the Murder of the President and the Attempt to Overthrow the Government by the Assassination of Its Principal Officers, Boston: J. E. Tilton, 1865.

Steers, Edward Jr., Blood on the Moon, Lexington, KY, University of Kentucky Press, 2001.

Taylor, Dave, Lincoln Conspirators website: https://lincolnconspirators.com.