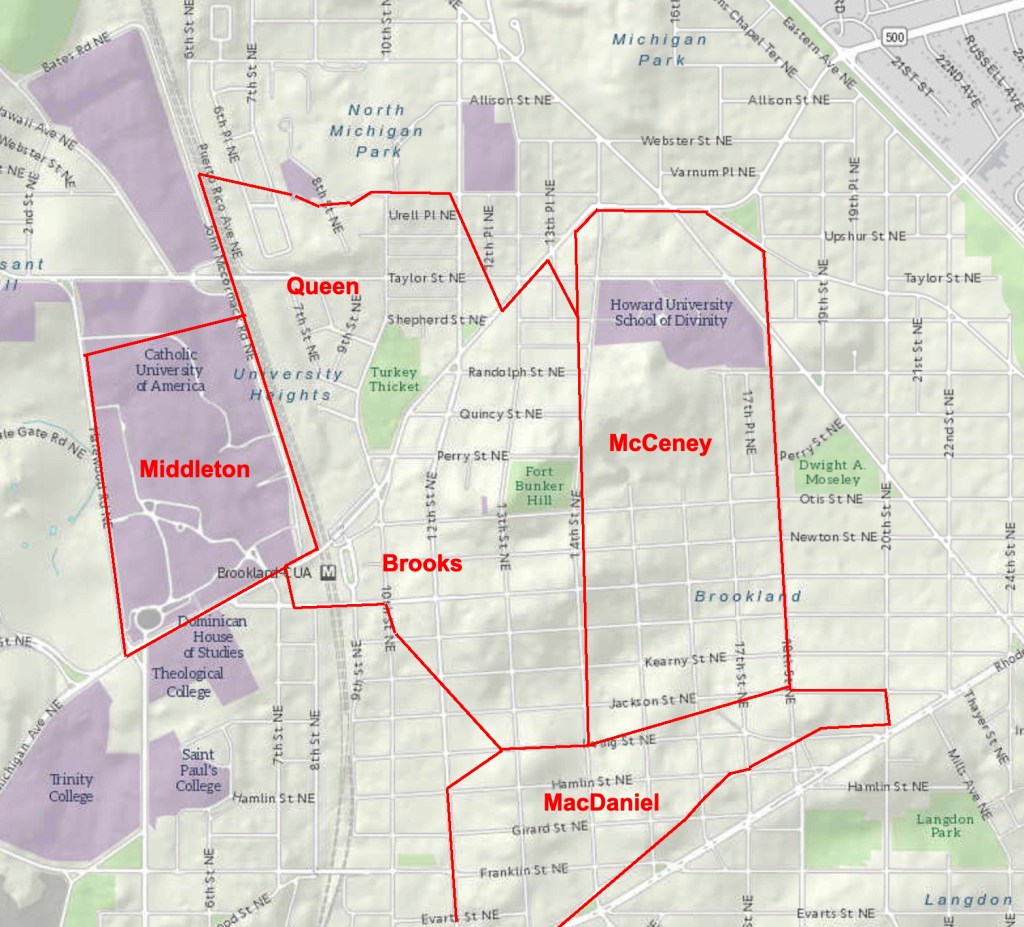

If you’re interested in the local history of this area, you probably know some of the prominent names from the pre-Brookland days: the Queen family, the Brooks family, the McCeneys, the Middletons. They owned this land, but the people who cultivated it, who built the houses and plowed the fields, who cooked and cleaned and cared for the children had names that hardly anyone knows. The Gutridge family, the Taylors, the Shaws, the Turners, all were large family groups, held in bondage by the area’s various landowners at the time the Civil War broke out. We know their names only due to an Act of Congress signed by Abraham Lincoln on April 16, 1862. That date is celebrated as Emancipation Day in the District of Columbia.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That all persons held to service or labor within the District of Columbia by reason of African descent are hereby discharged and freed of and from all claim to such service or labor; and from and after the passage of this act neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except for crime, whereof the party shall be duly convicted, shall hereafter exist in said District.

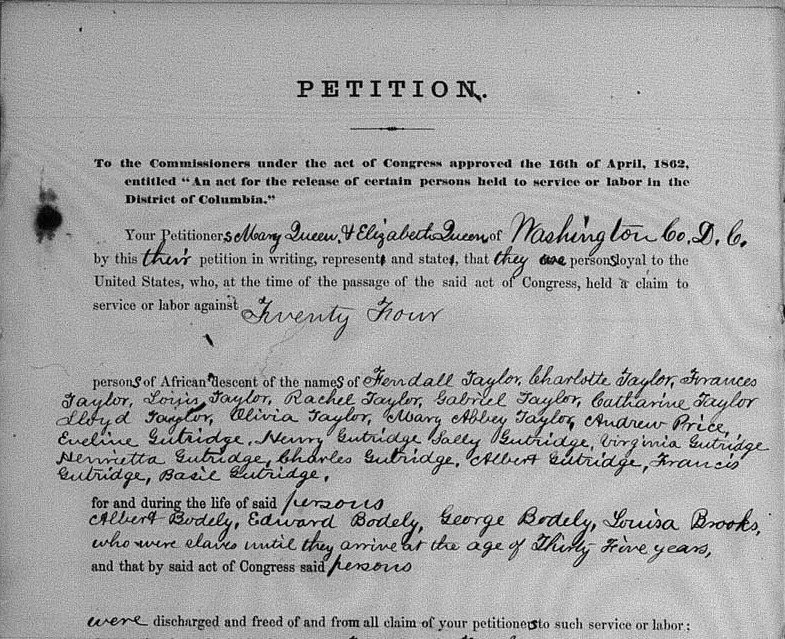

Formally it was called “An Act for the release of certain persons held to service or labor in the District of Columbia,” but informally it was known as the Compensated Emancipation Act. (click on image at right to see full document). A forerunner of the Emancipation Proclamation which would come in the next year, the Compensated Emancipation Act primarily did two things: it freed the enslaved people in DC, and paid the slaveowners for their loss. The owners had to swear loyalty to the Union and submit petitions if they wished to be compensated, and those petitions can be quite detailed, usually giving a physical description, skills, and both first and last names for the enslaved persons, something rare in American records. Having that data allows us to see the grouping of family names, and it appears many of the enslaved families had been able to stay relatively intact. I will list them by the farm on which they worked.

Queen/Brooks Farm

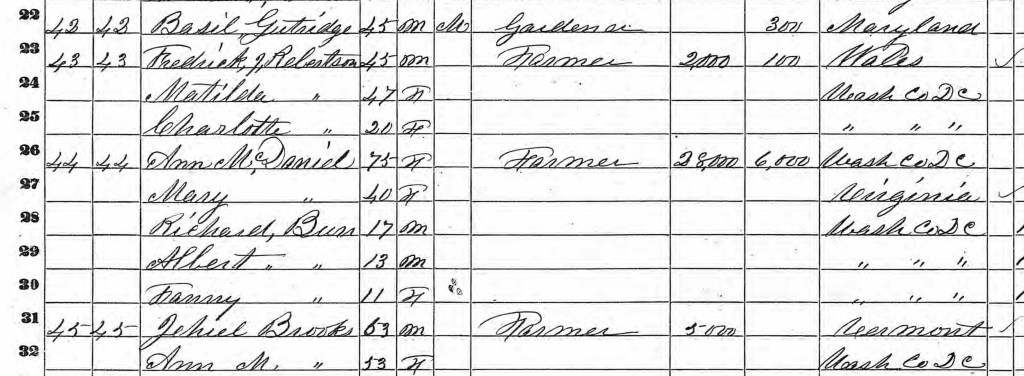

The Queen family held more people in bondage than anyone else in our immediate vicinity, 24 of them. Under the control of Mary and Elizabeth Queen, the enslaved workers were shared with the eldest Queen sister, Ann, the wife of Jehiel Brooks.

There are two large enslaved families on the Queen farm. The first is the Taylor family, headed by Fendall, with his wife Charlotte and their children Frances, Louis, Rachel, Gabriel, Catharine, Lloyd, Olivia, and Mary Abby, who ranged in age from 21 to 5. Fendall was 47 years old, 5 foot 6, with “hump shoulders.” Charlotte, 40, “had the scrofula, when young, she now is in very good health, an excellent cook washer & ironer.”

Then there is the Gutridge family, with Eveline Gutridge the matriarch, along with eight children: Henry, Sally, Virginia, Henrietta, Charles, Albert, Francis, and Basil; they ranged in age from 23 to 5. And the father? It appears he was a free man also named Basil. A member of the 15th Street Presbyterian Church, one of the earliest black churches in the city, Basil Gutridge farmed a small plot of land close by Ann MacDaniel’s farm on Brentwood Road.

Ann Queen MacDaniel was the aunt of Mary and Elizabeth Queen, so it seems possible that she and Basil worked out an arrangement to sell him a small plot of her land so he could stay close to his family on the Queen farm while he earned money to purchase their freedom. Three other people, Margaret, Cornelius, and Sarah Frances Gutridge, were enslaved on the Charles Wiltberger farm near Fort Totten and were likely related to this family.

There were also three young men named Bodely on the Queen farm: Albert, Edward, and George who were brothers, as well as a few individuals with no obvious family connections. The Queen sisters asked for $19,000 in compensation for the 24 people they held in bondage. Admitting that Charlotte Taylor had been sick, Mary Queen added, “The other servants I believe to be sound and healthy, They are all strictly moral and honest, some of them practical members of the church, generally intelligent and capable to work and though the value of some may seem to be over estimated, it has been offered and refused, not wishing to part with them.” Owners placed a high value on their enslaved workers in hopes of getting greater compensation. The government calculation was much lower, averaging about $300 per enslaved individual. The Queens likely got around $5-7,000.

(Update: After posting this I was contacted by Sarah Harrigan, a Catholic University student researching the emancipation petitions. She pointed me to a source that gave the final compensation figures. The Queen sisters got a little more than I estimated, $8,256.30.)

MacDaniel Farm

Ann Queen MacDaniel called her farm Queensboro and lived in one of the more interesting houses in the region. She filed a petition for the Turner family; Thomas the father, with children Armstead, Lucy, Elizabeth, and Cecilia. Ann MacDaniel described Thomas Turner as a “Brick moulder, waiter, unsound in body, of immoral habits.” The children seemed to better suit MacDaniel’s expectations, all described as having “good morals.” One wonders about the specifics of Thomas’s habits and physical condition, but no further details are available.

One other person is included in the petition, a George Allen. In the body of the petition he is described as “a very fine Restaurant cook, market gardner & handy with all tools—of sound body & mind, and good morals.” There is a note added at the end about him.

The note says “Said George Allen was purchased merely and simply to prevent his being separated from his family, as they were owned by different persons, and he was sold to be sent to Georgia.” I dug a little deeper and was able to find the rest of George Allen’s family. After the initial Compensated Emancipation Act was signed on April 16, a Supplemental Act was signed on June 12 that allowed enslaved people to file on their own behalf if the owners were openly disloyal, or lived in Maryland while the enslaved workers lived in the District. The latter was the case with the Allen family. Sarah Allen, along with her children William Henry, Adam, and Sarah filed their own petition since the owner, J. Pottinger McGill, lived in Maryland and could not file for compensation. Their petition was approved and the Allen family was finally reunited.

McCeney Farm

George McCeney owned a large farm and filed a petition for 14 enslaved workers. They seem to comprise primarily two families, the Halls and the Pinkneys. Minta and Jeremiah Hall (“healthy, valuable Gardner and Salesman”) were the parents, along with daughter Caroline and grandchildren Jerilina and John Wesley. The Pinkney family was headed by Priscilla (“good Cook, Laundress, very honest and reliable housekeeper”), with her daughters Martha, Ellen, Priscilla, Maria, and Laura. There were two other workers who were not part of either family, Louisa Allen and Rachel Jackson. With so few men, the women are listed as “farm hand” and “garden hand” in addition to their cooking and laundering duties, working both in the fields and the home.

Middleton Farm

Erasmus and Ellen Middleton were successful farmers on land that is now the Catholic University of America campus. They filed two petitions, one under her name, and one under his. Together, they enslaved 9 people on their farm. Lucy Shaw at age 58 was the mother of four children, Augustus (Gusty), Dawson, Sidney, and Caroline. The other four workers were Sally Price, Gusty Jones, Anna Maria Smith, and Maria Louisa Dorsey. The standout here was undoubtedly the 27-year-old Gusty Shaw, based on Ellen Middleton’s glowing description:

“The said Gusty Shaw is an extraordinary valuable valuable man; being an excellent farmer, gardener and marketer. He now has, and for the last five years has had the entire charge and management of the Farm and garden of Mr. Middleton. He was of the value of $1800.”

Running a farm the size of the Middleton’s was no easy task, and Gusty’s expertise was well-known to all the local families. His older sister Caroline earned a harsher evaluation from Erasmus Middleton:

“Said Caroline Shaw is hypochondriack, but for that would be a most excellent servant, being a good Cook, Washer & Ironer—with her defect we nevertheless think her worth $300”

As part of the Compensated Emancipation Act, President Lincoln appointed a three-member commission to assess the petitions. They approved 94 percent of them, dismissing a few because the enslaved were too young, too old, or too sick. Those people were freed without any compensation to the owner. By the time the process was finished, nearly 3,100 enslaved people in the District of Columbia had been released from bondage. Most of them quickly left their former owners and looked for work downtown, departed the city and headed north, or joined the Army when they were able. Augustus Shaw was registered for the draft in 1863:

I only found one person, Gabriel Taylor, still working on the Queen farm in 1870, but now as a free man. All the rest had dispersed.

Eight months after the Compensated Emancipation Act was enacted and deemed a success, President Lincoln released the Emancipation Proclamation. It was not total emancipation, freeing the enslaved people only in states that had seceded. In loyal states, such as Maryland, slavery continued legally. It wasn’t until 1865, with the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution that slavery was finally outlawed throughout the United States.

Looking through the Compensated Emancipation petitions is a humbling and enlightening experience. Having such full descriptions of the enslaved individuals who lived and worked here gives a human face to those who have been faceless for too long. It also gives us a snapshot into the everyday lives of both owners and owned during the waning days of slavery. If there are descendants of any of these families that happen to read this post, I would love to hear from them and learn how their families evolved after the war.

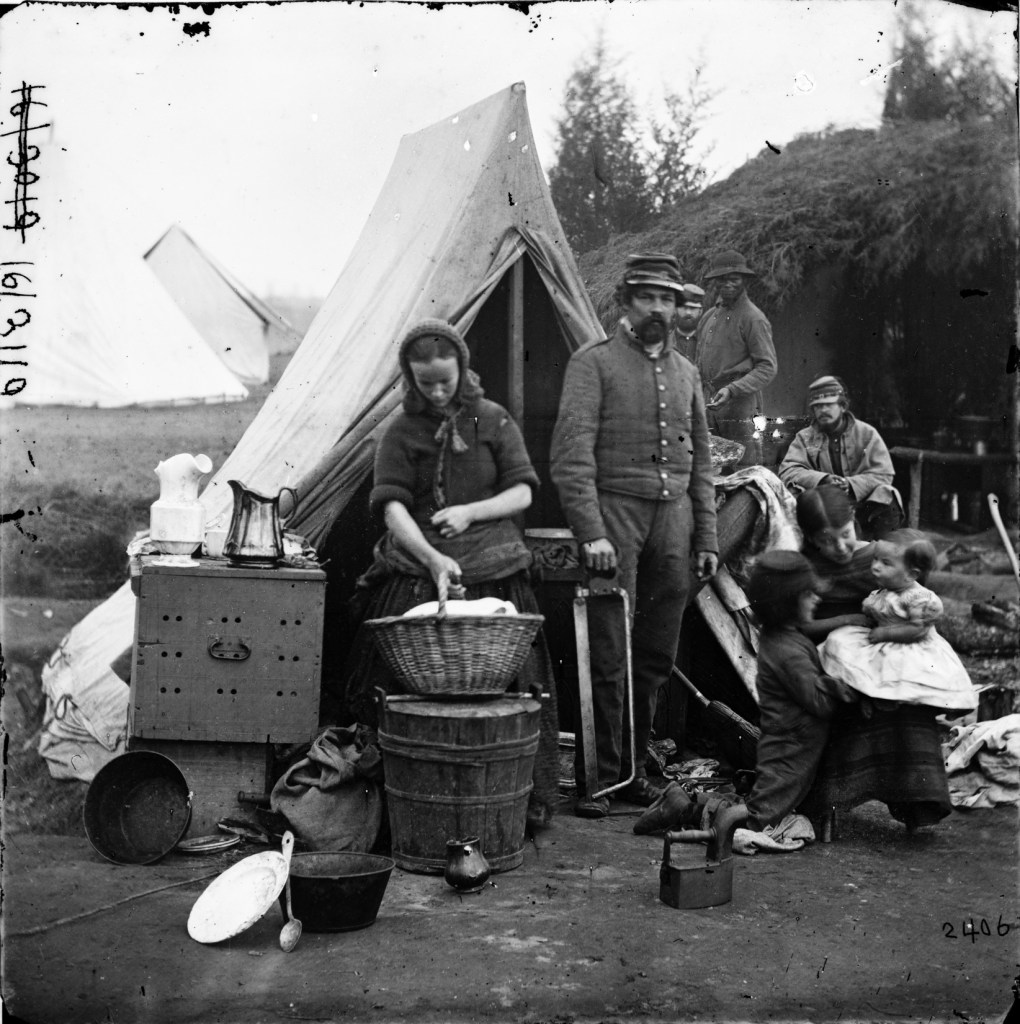

Unfortunately, there are no photographs to accompany the Emancipation petitions. There is one photo however, that may portray one of the people mentioned in this article. In late 1861, a photographer came to Queen’s farm to photograph the campground of the 31st Pennsylvania Infantry who were stationed there. One of the photos shows an African American man among the soldiers in the camp.

Many of the local slaveowners hired out their workers to help build the fortifications or cook and clean for the soldiers. Could this man be one of those held in bondage on the Queen farm? It is possible, but he could also be a servant that one of the officers brought with him to the camp, or a free man picking up some extra work. There’s no way to know. But to my eye there’s a self-assured look of determination on his face, perhaps the look of a man who knew that in a few months time he would be free forever.

Sources:

One website in particular was invaluable in my research for this post. Civil War Washington contains a treasure trove of information beyond the emancipation petitions. “Civil War Washington examines the U.S. national capital from multiple perspectives as a case study of social, political, cultural, and medical/scientific transitions provoked or accelerated by the Civil War.” It’s a site well worth exploring.

Civil War Washington, directed by Susan C. Lawrence, Elizabeth Lorang, Kenneth M. Price, and Kenneth J. Winkle, is published by the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln under a Creative Commons License.

National Archives and Records Administration, RG 21: Records of District Courts of the United States, Emancipation Records, 1862 – 1863. This series consists of petitions filed with the court as required by the District of Columbia Emancipation Act of April 16, 1862. Schedules filed within the first 90 days of the passage of the Act were recorded separately from those filed under the July 12, 1862 supplement, which extended the filing period to July 15, 1863. National Archives Identifier: 4314547 HMS Entry Number(s): NC-2 33

House of Representatives, 38th Congress, 1st Session, Emancipation in the District of Columbia. Letter from the Secretary of the Treasury, Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1864

Clark-Lewis, Elizabeth, ed., First Freed: Washington, D.C. in the Emancipation Era, A.P Foundation Press, Washington, D.C., 1998

Henley, Laura Arlene, “The Past Before Us: An Examination of the Pre-1880 Cultural and Natural Landscape of Washington County.” PhD dissertation, Catholic University of America, 1993

I’ve loved all your posts, Bob, but this may be the best yet; thanks!

LikeLike