The view from Fort Bunker Hill to Fort Slemmer

A few years ago I discovered a Civil War era photograph I thought depicted Fort Bunker Hill, despite its caption, which referred to Fort Slocum: “Washington, District of Columbia. Camp of 31st Penn. Inf. (later, 82d Penn. Inf.) at Queen’s farm, vicinity of Fort Slocum.” Queen’s farm refers to the farm of Nicholas Louis Queen, the patriarch of one branch of the extensive Queen family, and the father-in-law of Jehiel Brooks, for whom Brookland was named. The farm was located adjacent to Brooks’ property on the colonial tract known as Turkey Thicket. Today it is the Michigan Park neighborhood. After considerable research and consulting with a number of experts, it was determined the picture did indeed show Fort Bunker Hill shortly after it was built in 1861. Here’s the original post: https://bygonebrookland.com/2018/05/21/finding-fort-bunker-hill/

Ever since then, I regularly peruse the Library of Congress and National Archives websites, as well as other photographic repositories, to see if anything else local pops up. A while back I found this photo at the Library of Congress, and immediately thought it might show Fort Slemmer, the tiny fort on what is now Catholic University property.

It was labeled “Camp of 31st Regt. Pa. Vols. hdq. General Graham’s Brigade.” I remembered from my research on Fort Bunker Hill that the brigade camped on Queen’s farm was known as Graham’s Brigade, and included the 23rd and 31st Pennsylvania, and the 65th and 67th New York regiments. Excited, I started to examine the photo closely and then saw, scratched into the image along the bottom, the word “Murfreesboro,” a city in Tennessee. I assumed I had been wrong and didn’t research the photo any further. A few years went by until one day I was scanning through the National Archives Flickr page when I came across what appeared to be a print from the original negative. It was much more expansive, and didn’t have Murfreesboro etched into it.

The National Archives captioned the image “Camp scene and Fort (Perhaps near Washington)” and did not add much new information, other than it was photographed by Mathew Brady. I went back to the Library of Congress photo and found in the description this line: “Photograph copyrighted by Mathew Brady in 1861 as a part of series: “Brady’s incidents of the war.” That told me a couple of things. If the photo was taken in 1861, and if the caption was correct and it showed the camp of the 31st Pennsylvania Infantry, then it must be depicting Queen’s farm, since it is established the 31st was camped there from October, 1861 to March, 1862. Given that, I began to examine the image in detail.

A closeup of the fort shows a few things. Fort Slemmer had only three cannon, and two are plainly visible, with perhaps the breech of the third showing as well. As the forts in Washington were constructed, the soldiers laid tree branches, known as abatis, around the perimeter to deter ground assaults. There seems to be only a little bit in this picture (beneath the two cannon). Compare that to what it looked like a year or two later, when the fort was fully built:

This crisp, well-known photograph shows 2nd Pennsylvania Heavy Artillery troops marching out of Fort Slemmer, between rows of carefully placed abatis. The three guns were 32 pounder seacoast cannon on barbette carriages. For a closer analysis of Fort Slemmer, see an earlier post: https://bygonebrookland.com/2020/01/24/fort-slemmer-and-the-angry-florist/

To the far right of the photograph, a cluster of tents and some houses sit among pine trees.

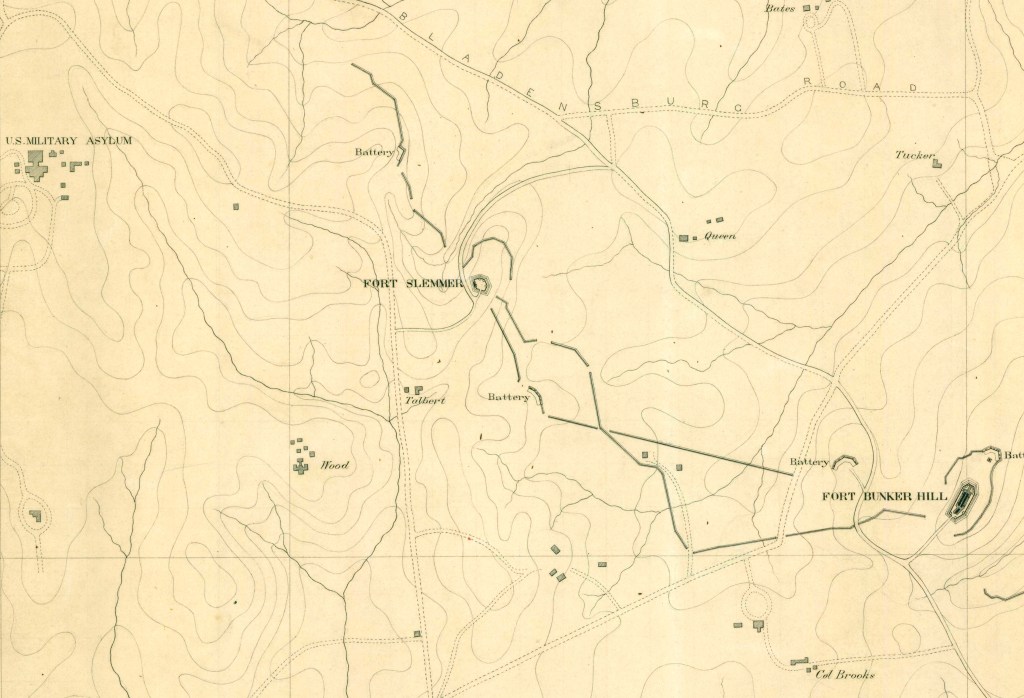

I believe that is the home of Nicholas Queen. Actually, Nicholas had died in 1860 and his son Henry took over running the farm. Still, most period maps show the name N.Queen or N.L. Queen, such as this one from 1867:

The Queen home was located at today’s 8th and Taylor Streets, in the Turkey Thicket apartment complex. I think the photo matches up pretty well with the above map as well as the map prepared by John G. Barnard, chief engineer of the Military District of Washington:

We also know that the Queen home was likely used as a headquarters by Graham’s Brigade, and also by the 2nd PA Heavy Artillery when they moved there in 1863. This excerpt from a letter written by Adjutant William Phillips in August 1863 contains some fascinating details, not only about the location, but his desire to get into the fighting.

No doubt you will notice that our Quarters is changed. We removed over here on the 13th of July. [Our] Headquarters is in a house of a Mr. Queen, between Forts Totten & Bunker Hill. [It is an] elegant place. Times are improving with me over here. Times & things go on so smoothly that only when I read the papers I know we are at war. It is going on 3 mos. since I handled a Rifle or cried “Here” to the “Roll Call.” If this is war, what is peace? I am very lucky also in the “grub” part. Being on the staff, I mess with the Commissary & Quarter Master Sgts. of the Brigade. [There is] plenty to eat of good things & a lady to wait on us. Big time, I assure you.

What really convinced me that the photograph depicted Fort Slemmer and Queen’s farm is on the far left edge of the photograph. It shows a large building perched on a hilltop, and a roofline with crenellations. Here’s a closeup:

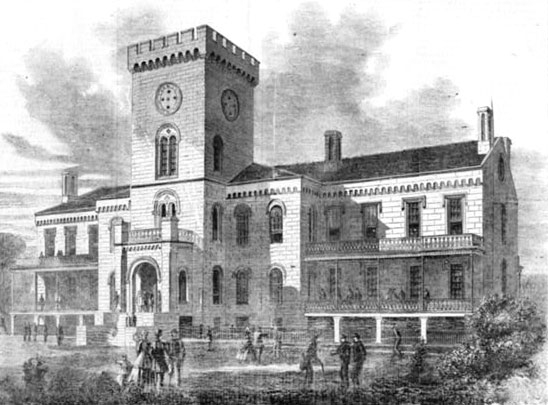

I believe that is the Scott building (now called the Sherman building) on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home. Here’s what it looked like in 1861:

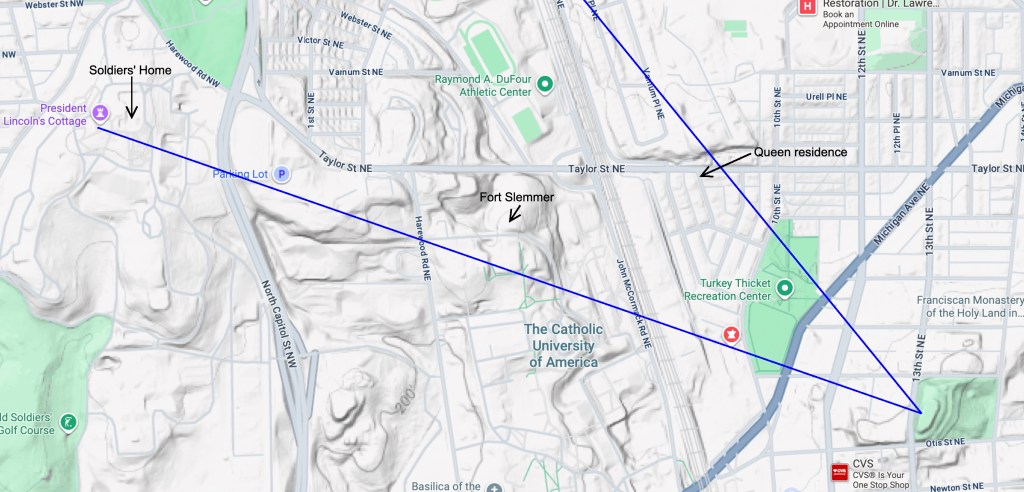

If the camera was perched on the slopes of Bunker Hill, maybe the parapet of the fort itself, pointing northwest toward Fort Slemmer, I believe both the Soldiers’ Home and the Queen residence line up very well. I overlaid the camera’s view on a modern map.

Compare that to the photograph, which I’ve labeled.

I wrote to three qualified historians, asking for their views. Bryan Cheeseboro, NPS Ranger for the Civil War Defenses of Washington thought that the fort looked too large to be Fort Slemmer. The two principal experts on Washington’s Civil War fortifications are B. Franklin Cooling III and Walton H. Owen II, co-authors of Mr. Lincolns Forts. Dr. Cooling thought it was hard to say and advised me to look over the J.G. Barnard maps of the period, which I did. Walton Owen, however, was quite sure the image does depict Fort Slemmer and the fields of Queen’s farm. It was the line of sight to the Soldiers’ Home that convinced him. He also thinks the branches at the bottom of the photo could possibly be the abatis surrounding Fort Bunker Hill. I agree with him.

Examining this photo was a fascinating research journey for me, and I believe the image shows us what the land around here looked like 164 years ago. You may want to zoom way in and look at all the soldiers gathered around in different groups. They are walking on ground that is now the Turkey Thicket Recreation Center, the baseball diamond and tennis courts, and the Turkey Thicket apartment complex. To me the photograph is like a time portal to a different era.

Sources:

Barnard, John Gross, A Report on the Defenses of Washington, to the Chief of Engineers, U S. Army Corps of Engineers, Corps of Engineers Professional Paper No. 20. Washington, DC: The Government Printing Office, 1871.

Barnard, John Gross and William F. Barry, Report of the Engineer and Artillery Operations of the Army of the Potomac from Its Organization to the Close of the Peninsular Campaign, New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1863.

Catholic University of America, Brooks-Queen Family Collection, website

Cooling, Benjamin Franklin and Owen, Walton H., Mr. Lincoln’s Forts: A Guide to the Civil War Defenses of Washington, White Mane Publishing Company, Shippensburg, PA. 1988

Cooling, Benjamin Franklin, Symbol, Sword, and Shield; Defending Washington During the Civil War, White Mane Publishing Company, Shippensburg, PA 1991

Dyer, Frederick H., A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, Dyer Publishing Company, Des Moines Iowa, 1908

Henley, Laura Arlene, “The Past Before Us: An Examination of the Pre-1880 Cultural and Natural Landscape of Washington County.” PhD dissertation, Catholic University of America, 1993

History of the Twenty Third Pennsylvania Infantry, Birney’s Zouaves, Three Months and Three Years Service, Civil War 1861 — 1865. Compiled by the Secretary, Survivors Association Twenty Third Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1903-4

Taylor, Greg, My Eyes Saw All-in Red and Flame, The Civil War Letters of William Beynon Phillips, 2nd PA Heavy Artillery, website, 2015

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service, The Civil War Defenses of Washington, Washington DC, 2004

Ward, George W., History of the Second Pennsylvania Veteran Heavy Artillery, from 1861 to1866, Geo W. Ward, Philadelphia PA 1904

Williams, Kim Prothro, Lost Farms and Estates of Washington, D.C., The History Press, Charleston, SC, 2018

Hi, this is fascinating. Do you think the line extending across the photo about 1/4 up from the bottom is Georgetown/ Bladensburg Rd, later Bunker Hill Rd, now Michigan Ave? I thought it might be but the big tree on the far left side seems to be too close to Fort Bunker Hill. I also wonder what you make of the white building to the right of the soldiers home. Thanks for all of your hard work exploring such cool stuff.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Actually, I think the road you’re talking about is the military road leading to Fort Bunker Hill. The view of Bunker Hill Road is blocked by the steep slope. The long fence line you see in the photo ends at Bunker Hill Road, out of camera view. As for the white building, I believe that is the Talbert home. It appears on all the period maps, and was situated on a rise adjoining Harewood Road, near today’s O’Boyle Hall on the CUA campus.

LikeLiked by 1 person